Avoiding Quit Point

My definition of engagement has changed a lot over the years.

My definition of engagement has changed a lot over the years.

When I first became a teacher, I wanted learning to be fun and enjoyable. I wanted my class to be the reprieve from the boring and predictable school day. I was inspired by Ron Clark who sings and dances for his students and Dave Burgess who incorporates elaborate hands-on activities that hook students, making them want to learn. I spent my summers, nights, and weekends coming up with my own original educational raps, designing games, and reconfiguring my room for elaborate historical simulations. I applied for grants to fund virtual reality (VR) technology so I could digitally take my students to the places we learn about. My class was dope. After all, I was the “cool teacher” with a gaming PC and VR headsets and all the kids wanted to be in my class. It was a great feeling, a real ego-booster, but honestly a shallow motivator for learning. School should definitely be enjoyable but it also needs to be meaningful, not just entertaining.

I discovered the importance of making learning more meaningful when I traveled to Washington D.C. to learn about World War II and the Holocaust for three days at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. A central theme of the session was "How can something like the Holocaust happen?" The presenters claimed that genocide is not inevitable. Humans make choices, from government officials to common civilians, and those decisions can lead to great good or great tragedy. This professional development had a profound impact on me as a human and as a teacher. The weight of this session sat with me for days, weeks, months and I knew the heart of my teaching would forever change. As a history teacher, it became my duty to shape ethical citizens who are not indifferent to the sufferings of others, or to the violation of civil or human rights. It's my responsibility to help young people appreciate, protect, and defend our democratic institutions and values. I am accountable to democracy for teaching honest history so that students develop the empathy, discernment, and critical thinking needed to be a good person that makes good choices in society.

Attending Harvard's Project Zero was another pivotal professional development that shaped my educational philosophy. I spent an amazing week in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and learned how to teach for understanding, create a culture of thinking, and have students document and reflect on their learning. In Georgia Studies, we cover from Native Americans to modern-day Georgia. With that much content, it's easy to reduce history to a bunch of isolated, Jeopardy-style facts. My experience at Harvard led me to prioritize student understanding and making connections from unit to unit and from past to present. I also had students take control of their understanding by reflecting on their learning, documenting their thinking, and explaining how it evolved over time. Harvard's strategies complimented what I learned at the Holocaust Museum because in order for students to empathize with the past, they have to understand it.

As educators, it is important to understand the kinds of challenges students are willing to persevere through but also why and at what points they are willing to give up.

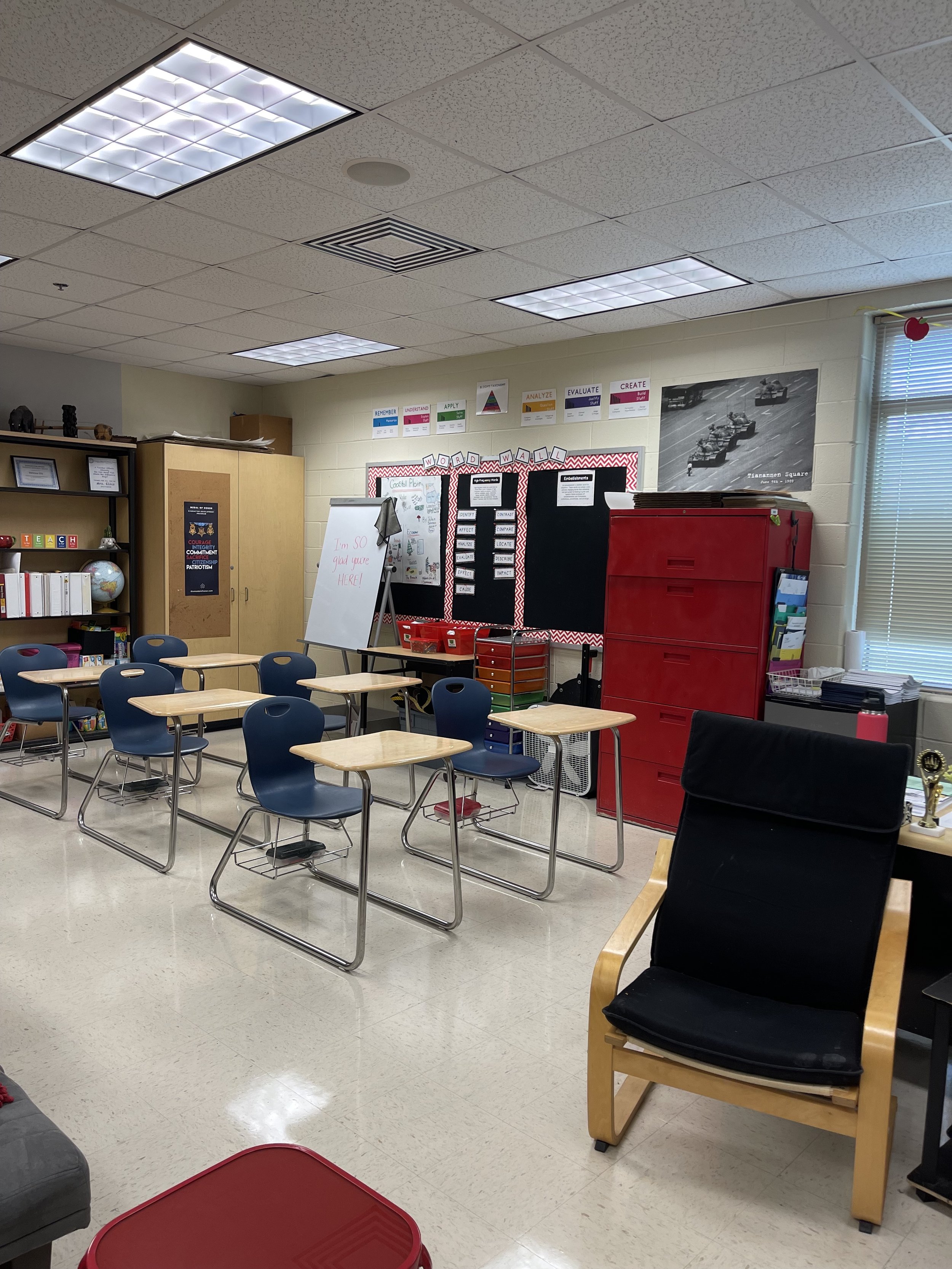

I needed to transform my physical classroom into a place that was fun and unique but more importantly supported meaningful learning and discourse between students. I've put in a lot of effort over the years into creating a space where students—and, frankly, where I—want to be. My classroom is designed with students in mind. I did research on adolescent development, conferred with colleagues who were successful implementing alternative seating, and asked for funding for new classroom furniture. My classroom now has a variety of collaborative and kinesthetic seating options that are flexible, improve intergroup relations, and promote positive social interactions. And I can change the groups and configurations based on what and how we are learning. With tables, wobble stools, couches, and desks, I can create unique grouping configurations which give students opportunities to get to know one another and engage in respectful dialogue. Given the tough topics I am mandated to teach in our history curriculum, it's important that my physical classroom supports the climate of my classroom—a safe space where students can be comfortable, collaborate, and learn.

I worked hard to make my lessons fun-filled, meaningful, and cooperative. And although students by and large enjoyed my class, I still had students who were apathetic, disengaged, and seemingly unmotivated. The question was why. If I was doing everything possible to engage students in the learning process, why then were so many giving up in the middle of class, or worse, outright quitting before they even entered my door?

Understanding Quit Point

In their book Quit Point: Understanding Apathy, Engagement, and Motivation in the Classroom, Adam Chamberlin and Svetoslav Matejic write about apathy, engagement, and motivation in the classroom. They claim that everyone, at some time or another, reaches a quit point—the moment when an individual’s productive energy toward a specific goal drops, causing withdrawal or minimized effort. As educators, it is important to understand the kinds of challenges students are willing to persevere through but also why and at what points they are willing to give up. When isolated to an academic setting, it is easy to view students as lazy or unmotivated. But kids apply sustained effort in any number of situations—sports, video games, new technology, hair and makeup, etc. And many show extraordinary resilience in their personal lives. They overcome food insecurity, abuse, depression, illness, and more, while still managing to come to school. When students aren’t engaging in their assignments, discussions, and projects, it isn’t because they don’t want to be successful. All students want to feel a sense of achievement and accomplishment in school. But based on their own experiences, quitting feels like the better option rather than struggling throughout the school day.

According to Chamberlin and Matejic, quitting exists on a continuum and can look different for each student. On one end of the spectrum, we have engagement. This is where the most learning occurs because students are actively participating, cooperating, and taking ownership of their education. When people hit their quit point, they begin to demonstrate forms of procrastination, distraction, or avoidance. This takes us to the middle of the continuum, effort rationing. Students feel they cannot or should not sustain a consistent, productive effort for the duration of a task so they try to display regular work habits even though their efforts have dropped. As a result, teachers may not realize that students are only simulating engagement and beginning to quit. Sustained quit is at the other end of the spectrum. This type of quitting is more obvious because students try to avoid any learning by sleeping in class, acting out, or refusing to attempt class work.

So what leads to students quitting in the first place? There are many variables that can influence quit point and those variables can shift from day to day, or even at different points within a lesson. Long-term variables are well established before students reach the classroom and come from experiences connected to their backgrounds. These variables can range from minor issues like a need for attention to major problems such as a lack of emotional and physical safety. Short-term factors usually happen unexpectedly but can still have a powerful impact on students’ quit points. Examples include an argument with a friend at school or trying to learn while sick. Understanding these variables is essential to understanding a student’s risk of quitting. Instead of lamenting the fact that students don’t work harder when experiencing one or many of these variables, Chamberlain and Matejic encourage teachers to structure their classes in a way that highlights existing student abilities. By doing so, educators can avoid more quit points and personalized instruction in ways that traditional educational frameworks have not widely considered.

In order to keep students on the engagement side of the quitting continuum, numbers, letters, and percentages need to be deemphasized or better yet, completely removed.

Limit Quitting By Deemphasizing Grades

The authors of Quit Point provide excellent suggestions for how to combat students’ quit points. They highlight developing a growth mindset, better planning and resource design, and empowering students through climate and culture. There is even a section of the book dedicated to assessment and grades! Traditional grades are incompatible with strategies to prevent quit points. Chamberlin and Matejic recommend focusing on the informative nature of assessment rather than the punitive nature of grading. Placing a heavy emphasis on grades distracts students from any other information teachers try to communicate. Instead of trying to improve, students just look for the next chance to earn points. Students use scores to justify effort rationing and quitting. If a student makes a passing score, they often see no need to view the teacher’s feedback. Instead of looking at all tasks as learning opportunities, lower-point assignments are relegated as “less important” than those with higher point values.

In order to keep students on the engagement side of the quitting continuum, numbers, letters, and percentages need to be deemphasized or better yet, completely removed. Gradeless formative assessment should be the focus. When feedback becomes information students can use to improve immediately rather than a number, teachers can use this assessment to help students increase the effort and energy they dedicate to learning. Chamberlain and Matejic believe that the goal of formative assessment should be similar to that of coaches and music teachers who do not wait several days to communicate their evaluation of players or performers. It is more effective to provide lots of opportunities to practice and observe students in the process of working instead of when they are “done.” And rather than average scores together, the Quit Point authors approach learning as a continuum of content, skills, and depth. Once students show understanding of the material, they can start focusing on skills, such as communicating a more extensive range of knowledge. Those who show a firm grasp of the content and skills are ready to work toward higher-level thinking and a greater depth of understanding.

Conclusion

The way I view engagement has grown and evolved. I started with the well-intentioned, but shallow, focus on fun. With phenomenal professional development opportunities, I worked hard to transform my lessons and classroom to support meaningful, relevant, and collaborative learning. But I was the architect of my educational philosophy and classroom design. Where was student input? How could they have more ownership in their learning? With knowledge of quit point, I am better equipped to meet my students where they are, move them into more productive phases of the quit continuum, and engage all students to learn. I won’t deny that post-pandemic apathy has been a challenge but relative to traditional grading classrooms, the majority of my students thrive in our grading-less context.

My students are in charge of tracking their mastery for each social studies standard, reflecting on their learning, and coming up with a personalized plan for improvement. I've deemphasized the power of numbers, letters, and grades, and elevated learning and growth. Students re-do and resubmit assignments using teacher or peer feedback to show progress towards the learning targets. By the end of the first semester, revision and reflection become a natural part of the learning process for students rather than compliance to my requirements. Students are given the power to evaluate their own work, revise when needed, and give themselves a grade. With a personalized learning framework, students are doing the heavy lifting of thinking, learning, and driving their education.

This is real engagement.

Vanessa Ellis currently works as an 8th grade social studies teacher at Veterans Memorial Middle School in Columbus, Georgia. She is the 2022-2023 Muscogee County School District Teacher of the Year. She enjoys creating educational songs based on popular hits and finding other ways to make learning fun and exciting. You can get a glimpse into her classroom on Instagram and Twitter. She currently resides in Midland, Georgia, with her husband (who is also a teacher) and their three children.